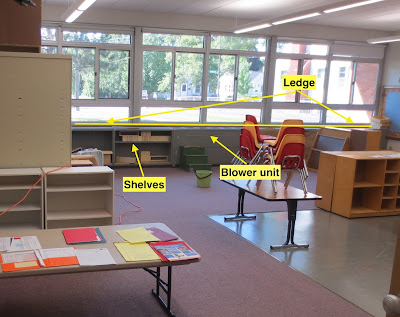

My classroom was an old elementary classroom with a bank of windows for one wall. Underneath the widows was a 12-14" ledge. The ledge was designed to accommodate a blower unit and extra classroom shelves.

I purposely decided not to put anything on the ledge because I wanted the children to be able to see out. Before long, though, the children appropriated the ledge for their play.

The empty ledge became an invitation for the children to line up the animals or to drive the little cars. This ledge was an intriguing space because it formed a long horizontal plane on which to play. In addition, the space was at shoulder level so they could play standing up.

The empty ledge became an invitation for the children to line up the animals or to drive the little cars. This ledge was an intriguing space because it formed a long horizontal plane on which to play. In addition, the space was at shoulder level so they could play standing up.

I still wanted the children, especially the toddlers, to be able to look out the window so I added a set of homemade green steps in front of the blower unit.

It was not long before the children appropriated the steps for their play. It made a great platform to test their jumping skills or to make a home for a family. Again, the steps offered an intriguing space with multiple levels.

By providing the steps to look out the window, I also provided easy access to the ledge itself.

As a consequence, the ledge morphed into a place to build with the colored blocks in the window sill or to have a tea party with a friend.

The ledge became a place to hangout and read or to sit during our group story and song time.

One of the big surprises for the children and myself was blower that was part of the ledge. Though it was the heating unit in the winter and would blow hot at times, most of the time it circulated the air in the room. The children did learn to be careful when it was hot, but otherwise they found the blower offered plenty of opportunity for impromptu scientific experiments. In the video below, the child took a scarf from the house area and placed it over the blower to see what would happen.

Here was another experiment some children tried. They stood over the blower in their dress up clothes to feel and watch their dresses flutter in the air.

Once I made that decision that it was OK for the children to work, stand and play on the ledge, it became one of the

most important play spaces in my classroom. They experimented and explored the space; they conquered the space. This became their space that they appropriated in ways that I could never have imagined.

What decision would you have made? In any case, this is just the beginning of how they appropriated the ledge for play. Wait until you see part two.